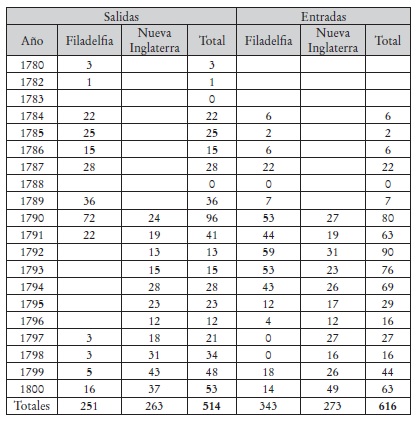

The 1790s provided the newly created republic of the United States with a commercial impetus during the early years of the 19th century that would contribute to the development of the new nation. Independence brought an end to the policies of exclusivity and the opening of colonial ports, particularly Spanish and French ones. Contrary to what might be thought, trade between the Thirteen Colonies and the ports of the Iberian Peninsula did not come to a standstill; ports such as Philadelphia intensified their traffic with Cadiz and Lisbon. Navigations, especially to Cadiz and through the Strait of Gibraltar, were not without risk. The concentration of maritime traffic in the ports of Philadelphia, Salem and Marblehead is reflected in this table, both for vessels leaving and arriving from US ports. The discrepancies between the number of departures and arrivals betray the inclination of American capitals to visit different ports on their voyages, so that ships leaving Salem for any Spanish port returned from other European ports. The distribution of traffic was fairly homogeneous: between 17880-1800 the majority of American ships went to Cadiz and Bilbao (49.7%), although with substantial differences in the origin of vessels. To Cadiz they came mainly from Philadelphia and to a lesser extent from New England, while Bilbao was more frequently visited by ships from the latter area. Tenerife especially received American ships arriving from Philadelphia, and La Coruña received those coming from New England. The commercial links between specific areas are undoubtedly determined by the demand and supply of goods. Cadiz’s relationship with Philadelphia and, probably with Baltimore and Charleston, stems from the need to supply cereals and flour, both for the surrounding area and for subsequent distribution. In Tenerife, the commercial activity of the American ships that transported the flour to the island, part of the merchandise was re-exported to Cuba. However, the table shows 50 ships that did not declare a specific port of destination, stating only their intention to travel to Spain. Most of these left Philadelphia in 1790 (38 of them). Another fact to bear in mind is the lack of interest on the part of American captains in voyages to Spanish Mediterranean ports, which may have generated some dissatisfaction on the part of the American government when, from 1786 onwards, it took a stand for control of the Moroccan corsairs.

Collection: Statistics

Project: 2. Social and economic impact of technological revolutions in Europe., 9. Travels and travelers: economic, social and cultural connections.

Chronology: XVIII, XIX

Scope: Secondary Education, Baccalaureate, University

Link: https://revistas.usal.es/index.php/Studia_Historica/article/view/shhmo2020421165193/22500

Resource type: Statistics

Format: Table

Source: Carrasco González, Guadalupe, «Vino, sal y pasas por harina pescado y duelas: el tráfico marítimo comercial estadounidense con España a finales del siglo XVIII (1780–1800). Una primera aproximación, Studia Historica, Historia Moderna, 42, 1 (2020), pp. 165–193.

Language: Spanish

Date: 2021

Owner: Álvaro Romero González (Modernalia)

Copyright: © Guadalupe González Carrasco © Revista Studia Historica, Historia Moderna

Abstract: Ship movements between Spain and the United States in the late 18th century

Image

Tags