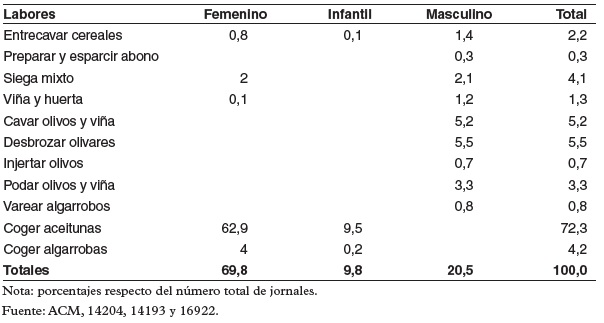

In recent years, there has been an extensive historiographical debate on women’s participation in rural professional markets and on the wage gap between men and women before 1800. At the same time, there is also no consensus on the wage share of farm household income. However, wage studies have shown that women were paid significantly less than men for the same work. This gap persisted throughout the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, although it narrowed moderately during periods of intense labour demand. The S’Estorell estate was located in the parish of Binissalem, at the foot of the Tramontana mountain range, and was the largest estate in the municipality and one of the ten most profitable on the island, with a valuation of 52,000 pounds according to the land registry of 1685. It covered 520 hectares, occupying the valley of Almandrá up to the first peaks of the mountain range in the villages of Alaró and Selva. In the mid-17th century, on the Safortesa estate, salaries were paid in cash, in current money or in kind when they were of a mixed nature. In some years, wages were paid in kind, in wheat at the request of the labourers. Payments for extra work were recorded separately from the agreed wage. On the other hand, the tasks of grafting and pruning were considered the most skilled, as both were paid with a mixed wage consisting of a monetary wage and a supplement in kind called companatge (condumio), consisting of a casserole with vegetables, accompanied by salted fish or cheese, wine, oil and bread. The master was paid 6-8 salaries a day, depending on the type of tree; his assistants received 4 salaries a day. The cost of companatge was 1.5 sueldos/day in the above-mentioned years. In the middle years of the 17th century, pruning was not as important as it became in later periods, when the olive trees were mature and their yield depended on more energetic pruning. The wage in this case was 51% lower than for grafting and 29-39% higher than for digging the roots. However, the range of women’s wages was narrower: seasonal workers received a mixed monthly wage, part in money and part in oil, plus other supplements such as accommodation, firewood, water and transport to and from their residence to the farm. The wage for picking olives was 20% higher than the one for digging in the pedios. In short, the wage gap for similar work (digging cereals) in the highlands and plains was still very high, with women’s wages representing less than 40% of men’s, figures very similar to those of the mid-16th century.

Collection: Statistics

Project: 3. Rural world and urban world in the formation of the European identity., 4. Family, daily life and social inequality in Europe.

Chronology: XVII

Scope: Secondary Education, Baccalaureate, University

Link: https://www.historiaagraria.com/FILE/articulos/RHA80_jover_pujadas.pdf

Resource type: Statistics

Format: Table

Source: Jover–Avellà, Gabriel y Pujadas–Mora, Joana María, «Mercado de trabajo, género y especialización oleícola: Mallorca a mediados del siglo XVII», Historia Agraria, 80 (2020), pp. 37–69.

Language: Spanish

Date: 2020

Owner: Álvaro Romero González (Modernalia)

Copyright: © Gabriel Jover-Avellá, ©Joanna María Pujadas-Mora © Revista de Historia Agraria

Abstract: Wage gap in a Mallorcan region in the 17th century

Image

Tags